Blood groups

There are 4 main blood groups – A, B, AB and O. Your blood group is determined by the genes you inherit from your parents.

Each group can be either Rh-D positive or Rh-D negative. This may be called “Rhesus type” by your healthcare provider.

People who are Rh-D positive have what is known as Rh-D antigens on the surface of their red blood cells.

People who are Rh-D negative do not have the D antigen on their blood cells.

In Europe around 85 people in every 100 are D-positive and 15 in every 100 D-negative.

Why is the Rh D- type important in pregnancy?

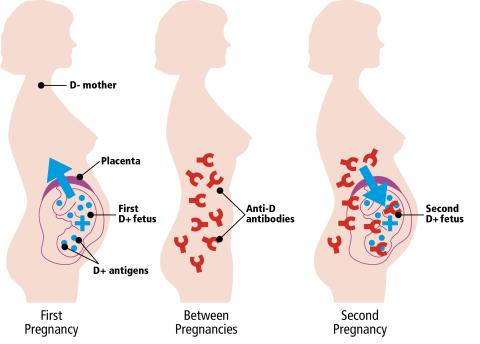

Babies inherit their blood type from both biological parents. This is important because if you are pregnant and have a D-negative blood group, it is possible the baby you carry will have D-positive blood group, having inherited this from the other biological parent.

However, it is important to know; it is possible even when one parent is Rh-D positive and one parent is Rh-D Negative, the baby may still be Rh-D negative based on how the blood group is inherited.

Inside the womb, the placenta usually acts as a barrier between maternal red blood cells and the baby’s. However, even in normal pregnancies small amounts of the baby’s blood may cross over into your blood stream. The most common time for a baby’s blood cells to get into your blood is when you give birth.

If any of the blood cells from an Rh-D positive baby get into the Rh–D Negative maternal blood stream, your body recognises the D antigen on your baby’s blood cells as a foreign protein and may produce antibodies to it.

This is called ‘sensitisation’. Any event or circumstance that could cause the pregnant patient to produce antibodies against the D antigen is called a ‘potentially sensitising event’ (PSE).

Examples of PSE include a miscarriage or termination of pregnancy, or if something happens during your pregnancy such as having an amniocentesis (a test to check if your baby has a genetic or chromosomal condition), chorionic villus sampling (genetic testing), vaginal bleeding or after abdominal injury such as a fall, a blow to your abdomen or trauma from a seat belt.

As a general rule, the first pregnancy that triggers this sensitisation, does not cause the baby suffer any adverse consequences, as it will already have been born by the time antibodies have developed.

However, if you become pregnant again with a D-positive baby, there is a possibility, the anti-D antibodies may cross into the baby’s bloodstream and attack the baby’s red blood cells.

This is called ‘haemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn’ or ‘HDFN’.

HDFN can be mild, but if more severe can lead to anaemia, heart failure, jaundice, brain damage, or even to the death of the baby.

With further pregnancies and further D-positive babies the risk of earlier and more severe HDFN increases and the outcomes can be more serious. This is why a preventative measure such as the use of anti-D prophylaxis is so important.

There are about 65,000 births of D-positive babies to D-negative pregnant people in England and Wales each year. It is estimated that, without routine preventative treatment, there would be over 500 problem pregnancies each year, leading to the deaths of over 30 babies and more than 20 brain damaged children.

Determining the unborn baby's blood group (fetal blood group)

A small amount of unborn baby’s DNA is present in your blood when you are pregnant. By detecting the baby’s DNA in your blood, it is possible to determine the unborn baby’s D blood group. This is the fetal RHD screening test.

If your unborn baby is predicted to be D negative, it is suggested you do not have anti-D immunoglobulin injections before or after giving birth. If your blood test shows that your unborn baby is D positive, or the result is inconclusive, you will be offered an anti-D injection.

Prophylaxis with anti-D immunoglobulin

Prophylaxis means giving a medicine to prevent something happening. Anti-D prophylaxis means giving a medicine called anti-D immunoglobulin to prevent you if you are D-negative from producing antibodies against D-positive blood cells, and so to prevent the development of HDFN in your unborn baby.

Thanks to prophylaxis with anti-D immunoglobulin, sensitisation during pregnancy and after childbirth can now largely be prevented.

Anti-D immunoglobulin is given with, your consent, as an injection, usually into the muscle of your upper arm or sometimes into a blood vein.

What exactly is anti-D immunoglobulin?

Anti-D immunoglobulin is made from the clear part of the blood, called plasma, and is from donors in countries outside of the UK. As with all blood products, donors are screened very carefully and the plasma is treated during manufacture so that the chance of passing on any infection is very low. There have been no reports of this happening.

Anti-D prophylaxis during pregnancy

a) Potentially sensitising events

In the event of potentially sensitising events such as the examples listed below, additional injections of anti-D immunoglobulin may be necessary:

- Coming or actual miscarriage

- Ectopic pregnancy

- Termination of pregnancy (abortion)

- Vaginal bleeding

- Obstetric interventions such as chorionic villus sampling, amniocentesis, or external cephalic version (ECV) in a breech presentation

- Abdominal (belly) injury e.g. after a fall, blow to the abdomen or a traffic accident

In order to reduce the possible effects of a sensitising event, it is crucial to report any events such as vaginal bleeding or abdominal injury to your midwife or doctor as soon as possible.

b) Routine prophylaxis

If you are pregnant and Rh-D negative, with no anti-D antibodies and a RhD positive baby, it is advised to have prophylaxis with anti-D immunoglobulin, even if they have already received anti-D for a sensitising event. This is known as ‘routine antenatal anti-D prophylaxis’, or ‘RAADP’. Depending on the dose given, you will either receive a single injection of 1500IU between the 28th and 30th week of pregnancy, or two lower dose injections, one at 28 and one at 34 weeks.

Anti-D prophylaxis after childbirth

After birth, your baby’s blood group will be tested. If your baby is confirmed to be D-positive, you will receive a further injection of anti-D immunoglobulin, ideally within 3 days of delivery. This is known as ‘postnatal prophylaxis’. If baby’s blood group has not been tested, or if there is any doubt as to the result, then you should receive anti-D.

Does everyone who is D-negative and pregnant need prophylaxis?

There are certain circumstances when this treatment may not be necessary:

- If you have opted for sterilisation after birth, though it may still be routinely offered

- If you are certain that the other biological parent of the child is D-negative

- If it is certain you will not have another child after the current pregnancy

- If your antenatal clinic offers a screening test to look for baby’s DNA in your blood that can show whether the baby is D-negative.

What should I do next?

If you are pregnant and have been told that you are D-negative, the person responsible for delivering your antenatal care (midwife, obstetrician or GP) should discuss anti-D prophylaxis with you and explain the options available so that you can make an informed choice about your treatment.

Anti-D prophylaxis (as a precaution) following miscarriage, termination of pregnancy or stillbirth

The loss of any pregnancy, for whatever reason, is traumatic for all those involved and there are many competing concerns following such a difficult time. However, it is still important to receive anti-D immunoglobulin, to reduce the risk of sensitisation and problems in following pregnancies. This is the case even when it is not possible to know the baby’s blood group.

Your midwife, nurse or doctor should discuss anti-D prophylaxis with you so that you are able to make an informed choice as to your treatment.

If you have any concerns, speak to a member of your healthcare team.

Additional information / side effects

You may develop a slight short-term allergic reaction to anti-d immunoglobulin; this can include a rash or flu like symptoms. Please get in touch with your GP or healthcare professional if you have any concerns.

Anti-D prophylaxis protection does not last forever, so you may need it in every pregnancy.

You may also find the following information useful:

With acknowledgement to NHSBT Patient Blood Management Practitioner Team, and CSL Behring UK Ltd for kind permission to use text from their anti-D leaflet.

Protecting you and your baby with anti-D immunoglobulin - patient information leaflet

Review due: April 2026